In recent years there has been a dominant theme in politics surrounding the economic narrative of Australia. It is a narrative portraying the Coalition as the responsible parents telling the public what is good for them after the irresponsible teens of the Labor Party stole dad’s credit card. Debt is bad surplus is good, so the story goes. The stern Coalition voices have constantly touted facts and figures around government debt declaring us intergenerational thieves effectively destroying the future of Australia with our selfish entitlement. There were theatrical tales of a debt crisis, government overreach, inefficiency, unemployment, deficit and WASTE!

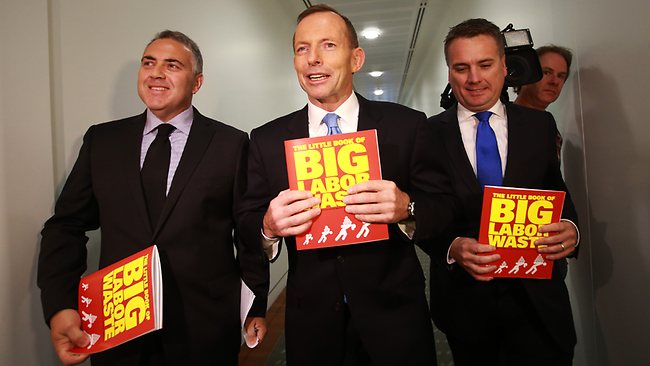

Source: News Limited.

Source: News Limited.

The Coalition politicians acting as economists were not speaking truths. They were using economic language, econospeak, to convey their thinly veiled ideology of class warfare.

The Great Australian economist Richard Denniss has been telling us that politicians have a tendency to not use econospeak in the way it was intended. Like Catholic priests of old who preached in Latin to an illiterate flock it is an act of smoke and mirrors. How can one question ideas that they don’t understand? It is a tactic designed to silence criticism. Econospeak similarly gives the elite some power of persuasion by inflating the importance of concepts such as public debt through a language most of the public do not understand. What the elites did not anticipate was that even if the Australian public don’t necessarily understand econospeak they do have a nose for recognising bullshit. Hidden within this language was an ideology of small government that protects the interests of business, the wealthy and social conservatives. The ideology soon proved to be an unpopular one.

This is not to say that Labor have never been guilty of the same. It is in the economic debate that the major parties rarely come to bipartisan agreement. Keating’s capital gains tax, the fringe benefits scheme, the GST, the carbon tax, the mining tax, just to name a few, show how economics has always caused a great divide. Economics is the issue where the continuation of class warfare is most apparent and both parties are able to flex their ideological muscle. The ALP fighting for middle and lower income earners and the Coalition favouring business interest and high-income earners. Both points of view have an important legitimate place in a democracy but has led to the politicisation of economics in Australia. Ideological economics has thus created polarised economic thinking beyond any notion of sound debate and critique.

The symbol of ideology in politics is delivered through carefully considered language. Econospeak is not ideological but as political language expert Marnie Holborrow says “all language has potential to be ideological”. Ideology is formed within language and when repeated from lofty heights of the media and politicians the representation of ideology acquires status through ‘natural truths’ and ‘common sense’. When the words such as “living beyond our means” and “reckless spending” reached the ears of the voting majority it seemed nonsensical to leave the ALP in charge of our finances. No one in their right mind would vote for a group who ignored such obvious ‘natural truths’ and ‘common sense’.

Another powerful use of language in public persuasion is the use of narrative. A debt crisis became the narrative for the Abbott opposition to steal away any dignity the Labor Governments still held after a tumultuous six year tenure. Creating this metaphor was masterful work from an opposition. By focusing on this metaphor that debt will be the destruction of Australia’s future masked the social impetus of the real issue at hand. The debt narrative became the invisible envelope of the Coalition ideology. Most tragically however is that it took focus away from the real issue of the Australian economy. The economy was slowing and we needed to do something about it.

Economists almost never agree on a healthy level of government debt. What they do agree on is that that a debt is bad surplus is good narrative has no place in a slowing economy. It is a simplification of a serious problem. Almost no economist would recommend spending cuts during the bust phase. Thus the Coalition were not referring to what the economy needs but what their interest groups and constituents want. As is often the experience of party politics, short term political interest trumps rational policy development.

Through the late 90s and the early 2000s Australia had enjoyed the longest unbroken period of economic growth of any developed country ever. This was a culmination of an increase in housing consumption funded by bank borrowing and international debts, export prices being much higher than import prices (‘terms of trade’ in econospeak), increase in resource investment and an extremely well timed Chinese resource demand that saved us from the global financial crisis. Thanks China. The Australian public became spoiled by increases in income, low taxation rates and we demanded more. The Government provided these spoils not through increased productivity of our economy but with the bounty of housing, resources investment and consumption increases.

By 2011 China began to tighten their resource loving belts and their resource consumption fell into a steep decline by 2013. Real expenditure and real income had grown extraordinarily high very quickly (real being econospeak for ‘adjusted for inflation’). This had made the Australian dollar more expensive for internationals than it had ever been before carrying serious consequences for our export sector.

This is what economists refer to when they speak about a ‘boom’. As is true for the natural science of physics however what goes up must come down and in economics this is called ‘the business cycle’. Although growth trends can be permanent in the long-run, short-run growth is slightly more tumultuous. A boom such as the one experienced in the resource sector of Australia then will be met with a ‘bust’.

During the hedonism of the resource boom Australians had spent in a way that assumed the good times were to just keep rolling in. Households spent their spoils and the Government cut taxes. Ross Garnaut eloquently names these the ‘Salad Days’. We are left with a high price level making it hard for many industries in Australia to compete internationally and impossible to maintain sustainable full employment. The ‘Dog Days’ phase in Australia is about facing consequences of our dizzying highs of the resource boom with a bleary eyed, headachy hangover.

It was the Dog Days that made the ALP fiscal management under Julia Gillard look so terrible. This spurred the inception of the debt narrative from the Abbott opposition and politicisation of debt heightened. Gillard and her treasury crumbled under the pressure of politics and made a premature promise of a Government surplus. As a result forecasting by treasury became terribly optimistic. As the deficit prevailed and forecasting was incessantly proved wrong the Gillard government started to look worse.

Along came Rudd 2.0. Having been forgiven by his colleagues and remaining a charismatic debater the election phase called on the leader it required. In Labor’s past charismatic leaders such as Keating had managed to sell “the recession we had to have” to the voters and Rudd offered a glimmer of such hope. Rudd shadowed Keating’s pragmatism and followed advice from the economists ignoring the debt metaphor. Three days before announcing the 2013 election Rudd made a large upgrade to the deficit. Unfortunately the powerful tool of language and metaphor had already dug its claws into the psyche of the Australian people and Rudd paid a high price in his credibility.

The debt metaphor success is not owed to a lack of intelligence of the Australian people. It is a part of our psychological make up to fall victim to such narratives. The battle between good surplus and evil debt showed an easy to follow logical economic theory for the voting public. Nassim Taleb in Fooled by Randomness argues that the world is not as homogenous as our psychology would like. As a result our brains go in search of patterns of causality that is much more simplified than any reality allows. Taleb argues that the destructive aspect of the media caters to our “heavily warped common sense and biases and is a plague on modern civilisation”. The same could be said of the endemic political ‘zingers’ resonating from the House of Representatives in Canberra. It is a prophet making roulette wheel indicative of the human need to simplify complexity. The zingers of federal politics tries to simplify extremely complex notions in just three words. Again the use of language proving to be a powerful tool in making ideology seem rationally plausible.

The truth about debt is that it is unavoidable. To use the turn of phrase intergenerational theft, such as Abbott did to the National Press Club, is not only wrong it is detrimental to good policy. With the benefit of hindsight we can now pinpoint this as the seed that grew into his catastrophic economic mismanagement and the political suicide of the Abbott government and his familiars.

Governments fund raise either through taxation or the issuing of bonds (shares in government debt that pays interest and promises a return at maturation). Since taxation is politically difficult and can have damaging effects on consumption the latter is quite useful in stimulating the economy. The current ten-year bond rate is at an all-time low of 2.55%. When government spending can enjoy such low interest repayments it generates a return greater than the cost of the bond (debt). To take advantage of such a bond rate is a very good idea. Another example of debt narrative politics trumping truth.

The thin veil of economics conveying ideology started to evaporate after the 2014 budget. The invisible envelope of the debt narrative could only last so long. The Commission of Audit report espousing GP co-payments and welfare cuts with no mention of increased taxes on superannuation or high income earners was a warning sign. Tony Sheperd who chaired the commission had made the decision that an average GP visit of 11 times a year had to indicate a high prevalence of paranoid hypochondriacs sucking medicare dry. It appears he either forgot how averages work, didn’t know how much a chronically ill person requires medical attention or has never read up on health economics (not surprising since he has no background as an economist). Preventative health measures like visiting the doctor benefits the economy far more than letting people become ill. This along with a few other examples sounded the alarm bells that this budget was not going to begin a journey to surplus. It was beginning a journey to a faulty and warped neo-conservative neo-liberal utopia.

The forewarning of the Commission of Audit report brought with it a budget that will go down in the history books as a collection of some of the most reviled policies in history. The budget reflected ideological priorities of the Coalition that sought to minimise debt only through meagre austerity measures that only targeted low income earners. $5 and $7 GP co-payments were not going to pay down government debt and given the revenue was to go directly to a medical research fund this policy would have zero effect of the government debt. And so the story goes as the budget was unpacked by commentators and outraged members of the public alike what was left staring them in the face was not in fact mature fiscally responsible policies but unfair policies. After incessantly touting a desperate need to cut government spending on pensions, welfare, health and education Joe Hockey’s first budget left the budget amounts spent on wealthy Australians relatively untouched. Through the muddied layers of econospeak an ideology was revealed and rejected.

The following budget saw a much more mild and positive Joe Hockey try to sell the notion that everything is fine. Not perfect but a much more logical approach than the previous year. Instilling confidence in the public encourages them to spend and invest. Consumer confidence had been seriously under-valued since it served no purpose in giving the Coalition a leg-up as leaders pushing their political ideology.

Politicians try to convince people that it is the market guiding their decisions. The truth is the market has no feelings. It is there to serve us, both as citizens and as consumers and will not predictively bend to political ideology. Political decisions have huge effects on cultivating an environment for economic growth. It is a political choice to spend billions on corporate interests keeping a mining industry alive that has seen its day. It is a political choice to not spend billions on investment in climate change abatement. It is a political choice to argue that doubling coal exports is necessary if we are going to be able to afford investment in renewable energy. These political choices as always are steeped in ideology.

Tony Abbott and his cohort were temporarily successful at selling a trumped up narrative of government debt crises because the Australian people were facing uncertainty. They were facing diminishing employment and income. The Coalition successfully sold them a bad idea by taking advantage of their confusion between causality and correlation in a slowing economy. Although language holds excessive sway in politics it does have limits. The rejection of the Abbott government’s economic management came from a recognition that it did not do what had been promised and did not represent an economic reality.

Who wrote this?

LikeLike

It was a piece I wrote for Uni, slightly altered.

LikeLike

Should submit it to the Guardian or Saturday paper. Sadly there is no further reason for you to listen to anything a polly says. Polly speak has been alive and well for decades. I refuse to read or listen to anything they say. Especially the lightweight modern ones.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Agreed, there is an art to deciphering their real intent though. In truth, the only politician worth listening to is a retired one.

LikeLike

Spot on. It’s amazing how much more honest (and somewhat more partisan) they seem when they’ve been out of the game a few years.

LikeLike